|

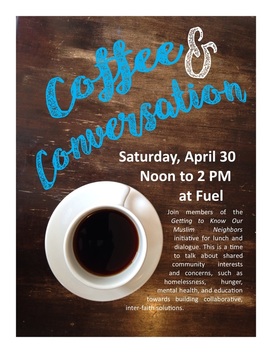

I am currently working on a photonarrative research project with a group of young Muslim Americans, mostly Purdue undergraduate, graduate, and medical students. This exhibit is part of a larger initiative that began with the intent of a) forming a network of church leaders who would be ready to respond in support of our local Muslim community if any kind of anti-Muslim demonstrations would take place and b) offer dialogue events at area churches. There have been a number of other outreach efforts locally, such as the "Meet a Muslim Day" and "Islam 101" and attention in local media to area Muslims. It is a timely topic given the rise of Islamophobia in response to political campaigns and media coverage of current events. My response has been guided by my Christian faith, a commitment which I believe offers an opportunity to relate to practicing Muslims; both concerned with building relationships and bettering our communities compelled by our personal faith. Ken Chitwood's article about a Christian response to Islamophobia requires more than education and instruction. A radical response to Islamophobia, compelled by the commands of scripture and the example of Jesus, demands developing relationships and interacting with Muslims. Moreover, it requires an experiential exchange between Christians and Muslims in America. Working on this exhibit is an example of this, and I hope will offer an opportunity for others in our community to begin to do the same. Asking individuals to share their stories and personal experiences - sometimes mundane recollections of everyday life, sometimes painful memories of being cast as an outsider and told that they do not belong here, and sometimes joyful in the kindness and empathy of others - is asking a lot. Asking individuals to share their lives through photographs is asking a lot. Their faces are known. And yet, the individuals I have the privilege of working with are inviting me into their lives and trusting me with their stories. As a researcher, and a Christian, it is a huge responsibility and one that I take very seriously. The exhibit opened at the Arts at Trinity event at Trinity United Methodist Church on April 10. Over 100 people attended the concert and exhibition, including several of the project participants. It is currently on display at Fuel Coffee Shop through the end of May. We have planned a Coffee and Conversations event (Saturday, April 30 at noon) where participants in the project will sit down with community members to discuss shared concerns and/or interests in our local community. Up to this point, the activities working towards our goal of offering opportunities for people to get to know their Muslim neighbors have focused on getting to know our neighbors as Muslims. The panel presentations offer a chance to learn more about Islam and the exhibit offers an opportunity to share experiences growing up and living as Muslim Americans. The community dialogues offer an opportunity to get to know our Muslim neighbors as neighbors – people who live in the same community, are concerned and passionate about the same issues, and dedicate their time to improving the health and well-being of their community. We’re hosting the first on Saturday, and are hoping to schedule a series of these events in correspondence with future panel presentations. Getting to know our Muslim neighbors as neighbors  Framing these events as inter-religious dialogue requires quite a bit of planning and thinking about how to create an open space for developing relationships across religious boundaries with humility, commitment, empathy, and hospitality. Catherine Cornille, a comparative theology scholar, has edited a volume on inter-religious dialogue, which she describes as different than other types of interreligious engagement with its actively constructive element and goals of mutual understanding, pursuit of truth and of personal and religious growth, which, according to Cornille, may take the form of deeper self-understanding, appropriation of new insights and practices, confession and repair of past misdeeds, or even the prevention of violence. In this collection, there is an essay by Mary Anderson that discusses the unique abilities of art as a form and expression of dialogue to create an interstitial space of intersubjective and intrasubjective exchange. She writes: It is a space of differential relation between self and other, aptly signifi ed by the prefi xes inter- and intra- and their Latin meanings: between, betwixt, in the midst of, among, mutually, with one another ; and, on the inside, within . Whether it takes place in the studio process between the artist and her material, in the viewer ’ s perception of a work of art, in religious ritual and veneration, or in the diurnal pieties of everyday life, true dialogue – like true art – is revelatory; it risks exposing the log in my own eye (cf. Matthew 7: 3–4, Luke 6: 41–2). At the level of spiritual experience, dialogue not only creates authentic bonds and engagement among its participants – the fruitful outcome of a genuine hospitality between the other and the self – it also becomes, in the course of this engagement, an intimate agent of creation, generating within its participants subliminal, incremental, and even sudden, changes in awareness of self, other, and world. Art and dialogue, as spiritual and thus embodied practices, incorporate this double aspect of creation... This capacity of art to limn between contemplative and active, intrasubjective and intersubjective, orientations makes it a particularly well suited resource for dialogue among religions, most of which have rich traditions of material culture. The difference of art – its beautiful, potent, and sometimes transgressive, otherness – has the ability to awaken uncharted pathways for understanding the increasingly multiple event called “inter-religious dialogue.” I am very much interested in the benefits of utilizing both art and conversation in our interreligious dialogic efforts, and making sure that we offer a triad approach - education, art, and engagement - with humility (a respect of other religions and faiths), commitment (to individuals, to working together, to one's own faith, and to tolerance), interconnection (recognizing common challenges), empathy (viewing another religion from the perspective of its believers), and hospitality. We have started to talk about doing this photonarrative research with Muslim American communities in other cities, something that I am very supportive of and willing to do. Continuing to investigate Muslim American experiences will offer an opportunity to seek out different perspectives, practices of Islam, experiences being Muslim in America (for example, just in the Lafayette project, the inclusion of a young woman who comes from the Nation of Islam is important. It is an often untold story within Muslim American experience, which is frequently dominated by Arab concerns and traditions). There are many networks of Muslims in America that are not necessarily included in the dominant Muslim American narrative, and we are seeking to add these. This is a long winded post, one began weeks ago, that, for me, marks the beginning of a burgeoning project. It is a personal project, as well as a professional one. It is research, it is art, and it is faith in action. I will be periodically posting updates about the project as it moves from city to city and as we continue to facilitate dialogues.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Ruth M. SmithCommunity arts educator and researcher. Drinking coffee. Home educating. Making art. Listening intentionally. Categories

All

Archives

February 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed